Fair Use in the Real World

By Mariah Lewis, Metadata Management Librarian, & Laura Childs, Emerging Technologies Librarian

Fair Use Week 2021

Fair Use Week is an annual celebration of the doctrines of fair use in the U.S. and fair dealing in Canada. These are limitations to copyright law that, under certain circumstances, allow people to use copyrighted works without permission from the owner. But why does that matter?

Copyright is like a coin. On one side of the coin are the exclusive rights granted to copyright owners, to protect their work and their ability to profit from it. On the other side are the exceptions and limitations (such as fair use) that allow people to use copyrighted works without permission from the owner. This is important for the creation of new knowledge and freedom of expression, especially in an educational setting.

As teachers and students, you are likely to be already exercising fair use daily, such as:

- Writing papers that quote, discuss, or reference copyrighted material

- Including photos of an artist’s work within a Powerpoint presentation

- Searching for words or phrases within Google Books

- Compiling clips of a film to create a commentary video

- Watching a documentary that features historical documents, videos, and photos

- Searching within a database to find articles that have been indexed

What is Fair Use?

Fair use isn’t just an option – it’s a right! You are entitled to exercise it.

“Notwithstanding the provisions of sections 106 and 106A, the fair use of a copyrighted work, including such use by reproduction in copies or phonorecords or by any other means specified by that section, for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching (including multiple copies for classroom use), scholarship, or research, is not an infringement of copyright.”

– Copyright Law of the United States (Title 17, Section 107)

Although it’s defined within copyright law, fair use isn’t cut and dry. It needs to be decided on a case-by-case basis. Fair use decisions rely on a balance of four factors:

- The purpose of the use

- The nature of the copyrighted work

- The amount of the material used

- The effect of use on the potential market for, or value of, the work

Court cases are an important part of fair use, because they influence future decisions and help set parameters for what is protected by fair use, and what isn’t. If you need to make a fair use assessment, looking at past legal decisions can help.

Keep reading to learn about four high-profile copyright cases and what they can teach us about applying fair use in our own lives.

Fair Use Court Cases

Case #1: Capitol Records v. Redigi

Verdict: Fair use not found

ReDigi was a platform that allowed users to download digital music, eBooks, games, apps, and software. It also allowed users to stream music. ReDigi claimed that all of the digital files on the website were both legally acquired and from an eligible source, which they argued made it legal to transfer the digital content from one user to another.

Capitol Records disagreed and sued ReDigi. In 2013, the courts sided with Capitol Records, finding that ReDigi violated copyright. Fair use was not found because:

- There was no transformative use by Redigi, and their service was only meant to be commercial, weighing against factor #1.

- The copying of the entire files (songs, e-books, etc.) weighed against factor #3.

- The files, identical in nature to those sold by Capitol Records, were competing directly with Capitol Records and causing them to lose sales. This weighed against factor #4.

Takeaways:

- Merely reproducing a copyrighted work does not make it a “transformative” use, even if legally obtained.

- The law does not define how much of a copyrighted work can be safely used, but in general, the more you use, the less likely it is to qualify as fair use.

- If the way you are using a copyrighted work could displace sales of the original work, or harm the future market for that work, fair use is less likely to be applicable.

Case #2: Dr. Seuss Enters., L.P. v. ComicMix LLC

Verdict: Fair use not found

ComicMix published a book titled Oh, the Places You’ll Boldly Go! The publication retold the story of Oh, the Places You’ll Go! by Dr. Suess using Star Trek characters and themes. At first, fair use was found by the District Court in 2019 because the new book was a highly transformative “mash-up” of the two works. However, Dr. Seuss Enters., L.P. appealed and in 2020, the 9th Circuit Court ruled that fair use was not found because:

- The commercial use of Seussian elements was not a parody, critique, commentary, or transformative in any other way, weighing against factor #1.

- The nature of Seuss’ work was highly creative, weighing against factor #2.

- ComicMix replicated a substantial amount of the original work, weighing against factor #3.

- ComicMix intended to capitalize on the same market as the original work, thus competing with the Seuss estate’s right to derivative works and weighing against factor #4.

Takeaways:

- Copying an existing work or its creative elements without adding new value in some way, such as critique or parody, will likely not favor fair use.

- Creative works typically have more copyright protection than factual works, so the more creative something is, the more risk there is in reusing it.

- The law does not define how much of a copyrighted work can be safely used, but in general, the more you use, the less likely it is to qualify as fair use.

- If the way you are using a copyrighted work could displace sales of the original work, or harm the future market for that work, fair use is less likely to be applicable.

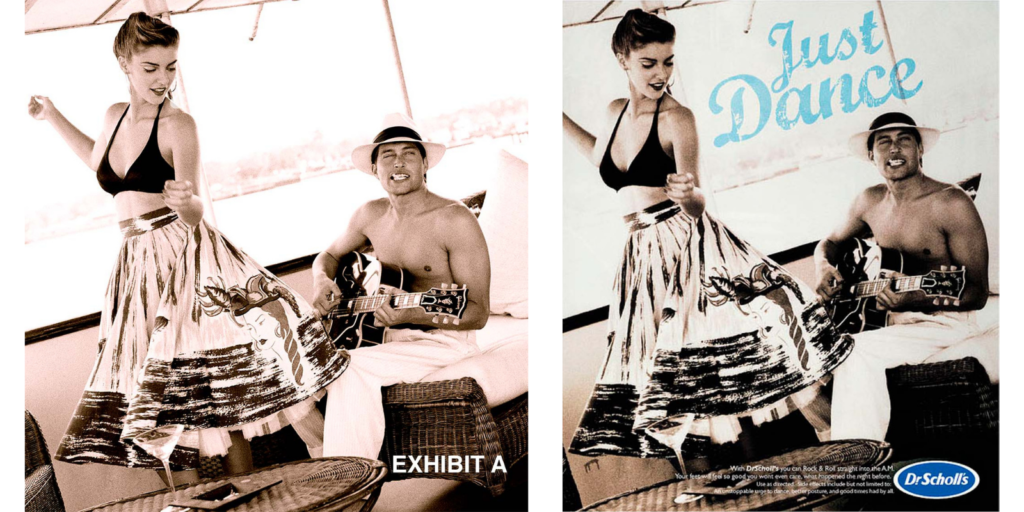

Case #3 Reiner v. Nishimori

Verdict: Fair use found

In this case, a student (Nishimori) at an art institute was given an assignment to use an existing photograph and create a mock advertisement with it. Their professor provided a selection of photographs, including a photo called “Casablanca,” taken by Reiner as a contractor of a stock photo company. The student who completed the assignment also uploaded it to Flickr in order to archive their classwork.

The photographer saw this image and sued both the student and the art institute for copyright infringement. However, the court ruled in favor of fair use because:

- The student’s use of the photograph was both transformative and for an educational purpose. His project transformed the purpose of the original photo by turning it into an advertisement. In addition, neither the student nor the school actually used the photograph in a commercial way. All of this weighed in favor of factor #1.

- The student’s image would not harm the potential market for the photographers work, weighing in favor of factor #4.

Takeaways:

- Though the educational purpose behind using a copyrighted work (as opposed to a commercial purpose) does not automatically guarantee a fair use ruling, the fact that the student was not selling his work supported his case.

- Transforming the purpose of the photograph was key to the fair use analysis.

- Not all of the factors weighed in Nishimori’s favor. In fact, the court felt that factors #2 and #3 were both against fair use because the original photograph was creative in nature and the student reused the photograph in its entirety. But because a fair use analysis weighs all four factors, the court determined that the remaining factors were strong enough to tip the balance. This shows the power of fair use as a copyright exception!

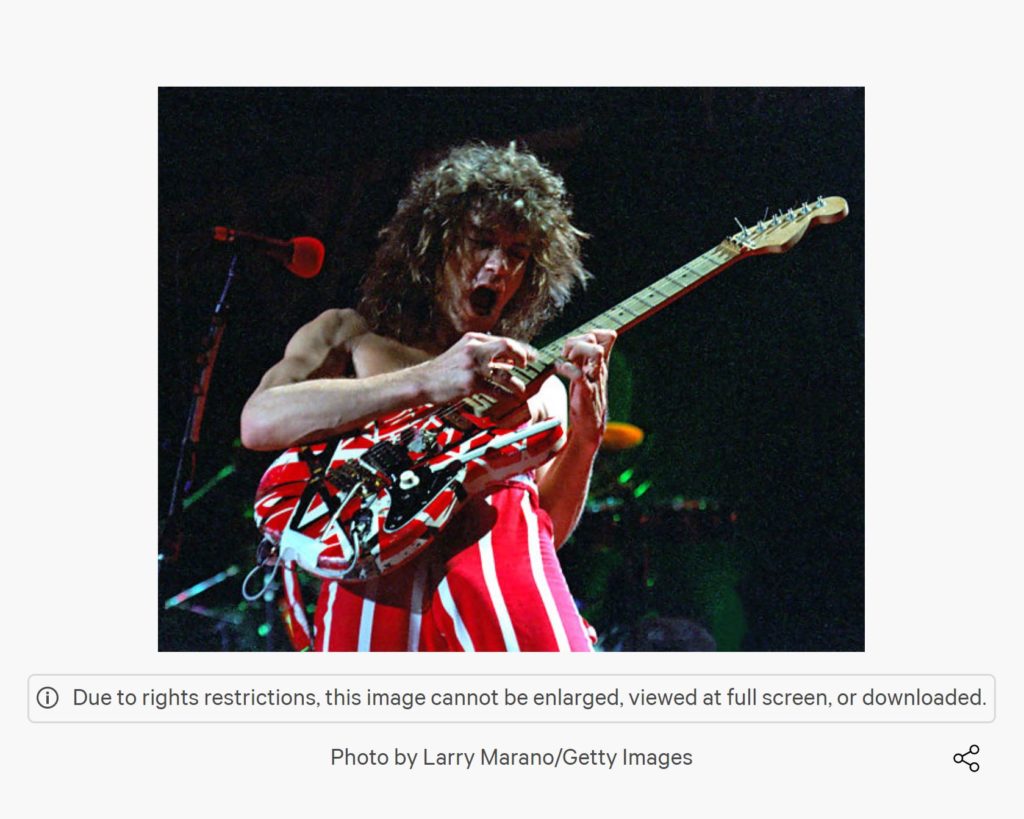

Case #4: Marano v. Metropolitan Museum of Art

Verdict: Fair use found

In this case, The Metropolitan Museum of Art put together an online exhibit guide for their Play it Loud: Instruments of Rock & Roll exhibition. The Met included a photo taken by Lawrence Marano of musician Eddie Van Halen playing the “Frankenstein” guitar, but the museum did not license the photo or request permission to use it in the guide. Marano sued the Met over their use of his image. However, the court ruled that The Met’s use of the photo was fair use because:

- The original photo was taken for the purpose of depicting Eddie Van Halen performing and his significance as a musician, while the Met’s guide used the photo in “a scholarly context as a historical artifact to contextualize the ‘Frankenstein’ guitar.” This weighed in favor of factor #1.

- The nature of Marano’s photo was creative, but the Met used it not for its creativity but for its historical value, weighing in favor of factor #2.

- The photograph was used in thumbnail format and as a very small component of the overall spread. The amount used was therefore reasonable in relation to The Met’s use of the image, weighing in favor of factor #3.

- The transformative nature of the use also meant that there was little or no financial gain in using the photo. The court determined that the Met’s use of the image fell into a ‘transformative market’ that would have no effect on the photographer’s market of Van Halen fans. This weighed in favor of factor #4.

Takeaways:

- In some cases, using an entire work can still be fair use if its purpose and nature are transformed.

- Transforming the purpose and nature of a copyrighted work can help prevent infringing upon the potential market for the original work.

How to Learn More

Excited about fair use yet? To learn more about fair use and an array of other copyright topics, visit the library’s Copyright Resource Guide. You can also use our Fair Use Checklist that can help you assess your use of copyrighted works.

If you are a faculty member or instructor, we also suggest viewing this webinar recording where we discuss fair use in the context of teaching. If you have specific questions or would like to schedule a consultation, visit the resource guide for contact information.